(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

A feared and beloved crime family patriarch relaxes on a compound surrounded by loved ones, there to celebrate a special occasion. There’s music, and one of the clan has brought along their significant other.

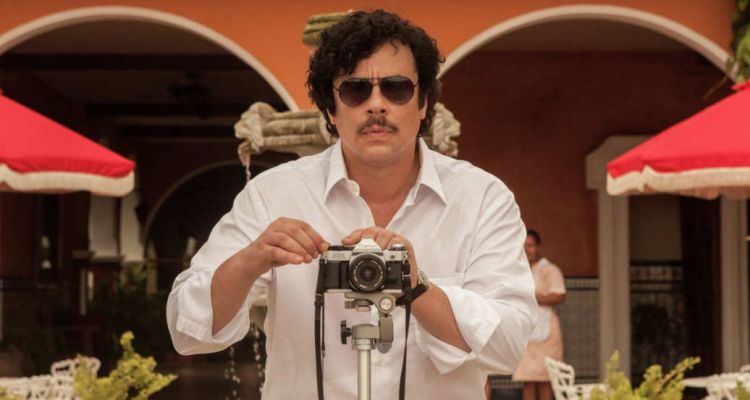

So far so The Godfather, though the setting of Esobar: Paradise Lost is more akin to the film’s 1974 sequel, the isolated townships, dirt roads, and tropical forests of Colombia. The patriarch in question here is none other than infamous drug lord Pablo Escobar (Oscar winner Benicio Del Toro) and, in the role of unwilling interloper Nick, Hunger Games’ Josh Hutcherson.

Medelllin, Colombia, June 18th, 1991. A frantically packing Nick is called away from his girlfriend Maria (Claudia Traisac) by armed thugs. Pablo wants to see him. Meanwhile, Escobar himself – we first see him back to us; a beard, hint of a paunch; enthralling – places a satellite call to his mother. He’s preparing to go to prison and seems concerned that God will forget about him.

The first half of Paradise Lost reveals exactly what brought these unlikely acquaintances together – their dynamic bears a passing resemblance to the central relationship in Kevin Macdonald’s Last King of Scotland. Escobar claims to see “Nico” as a son, but will that family connection be enough to keep him safe? A conversation that takes place in Bonnie and Clyde’s still bullet-riddled automobile, which Pablo has somehow acquired, is a potent memento memori and symbol of betrayal.

Despite its somewhat perfunctory title, Paradise Lost is a remarkably composed piece of work, especially for a first-time film-maker. Hutcherson’s Nick is a good kid, quiet and prepossessing, whose journey into the heart of darkness – again, Coppola’s influence is writ large here – is grounded in his willingness to blind himself to what’s going on, like the henchman washing blood of his legs at the family stables.

Warily respectful of “Uncle Pablo” from the off, his transformation from ingénue to unwilling accomplice would be less believable were it not for Nick’s evident devotion to Maria, sold by Hutcherson’s immediate chemistry with the Traisac. She takes a matter-of-fact approach to her uncle’s line of work, that is until the facade is stripped away.

While Nick’s moral conundrum forms the basis of the plot, the film revolves around the looming figure of its title character. Jokes aside that Entourage did it first, Del Toro’s Escobar is an intriguingly subtle creation: less Scarface than Che, his easy manipulative smile, heavy-lidded eyes, and deceptive focus give the impression of a Komodo dragon sizing up potential prey.

Whether taking instructing Nick on taking a life (“It’s easier if you don’t know anything about him”) or playing in the pool with his kids, it’s clear that this is a man of many aspects, largely un-compartmentalized. A killer who gives to charity, to the people of Columbia he’s a rock star, or the Pope, dispensing boxes of money from his limo and dispensing blessings with his fingertips. Other gangsters threaten people; Escobar threatens God. When Nick credits the Almighty for some recent good fortune Escobar is quick to disabuse him.

As director, Andrea Di Stefano’s use of soft focus evokes a nightmarish feeling of uncertainty and judicious POV shots, as in one truly menacing dog attack, help to immerse us in Nick’s increasingly compromised worldview. There’s a shot of Nick exiting a jeep, gun in hand, unseen by his unexpecting victim on the other side, which is repeated when the gloating Drago comes calling (Carlos Bardem) – a shot of whom evokes Brando’s Kurtz, squatting spider-like in Apocalypse Now.

On the topic of shadows, Luis David Sansan’s cinematography rivals Prince of Darkness Gordon Willis’ for its ability to meld light and dark – bright days that are somehow overcast, shadows that enhance rather than obscure. As writer, Di Stefano is insightful but never revelatory: Nick is put under pressure, Escobar is exposed in his many facets, but neither are illuminated.

With committed performances from its leads and a virtuoso debut from Di Stefano (Max Richter’s quietly foreboding string score also merits a mention), Escobar: Paradise Lost lets us down only in its final act. The film abandons one character to a peremptory fate – though perhaps not the one you’d expect – and is unable to bring another’s to a close.

If never quite living up to the impossible standard set by The Godfather, Di Stefano nevertheless manages to craft a grueling thriller that finds a way to comfortably exist – indeed thrive – within the shadow of Coppola’s masterpiece.