(3.5 / 5)

(3.5 / 5)

With its overwhelming presence in our everyday lives, it’s easy to forget that film – in fact, media in general – is a medium still in its infancy.

It’s been less than 120 years since the first motion picture was displayed before an audience. The Renaissance, for instance, lasted almost three times as long as cinema’s been around. As such, any work of cinematic fiction that seeks to comment on this far older, more developed art form has to negotiate, however implicitly, this divide, comparable, perhaps, to the divide in years between father and son.

That uneasy segue takes us onto the subject of French auteur Gilles Bourdos’ newest film, Renoir, namely the relationship between Impressionist Auguste Renoir and his son, filmmaker Jean Renoir, both luminaries in their respective fields.

Renoir, however, centers around an altogether different figure: that of one of the elder Renoir’s models, Catherine Hessling, who arrived at his estate in Cagnes-sur-Mer in 1917 and remained with him till his death two years later. It wasn’t until some months into her stay that Jean returned home, injured, from the war.

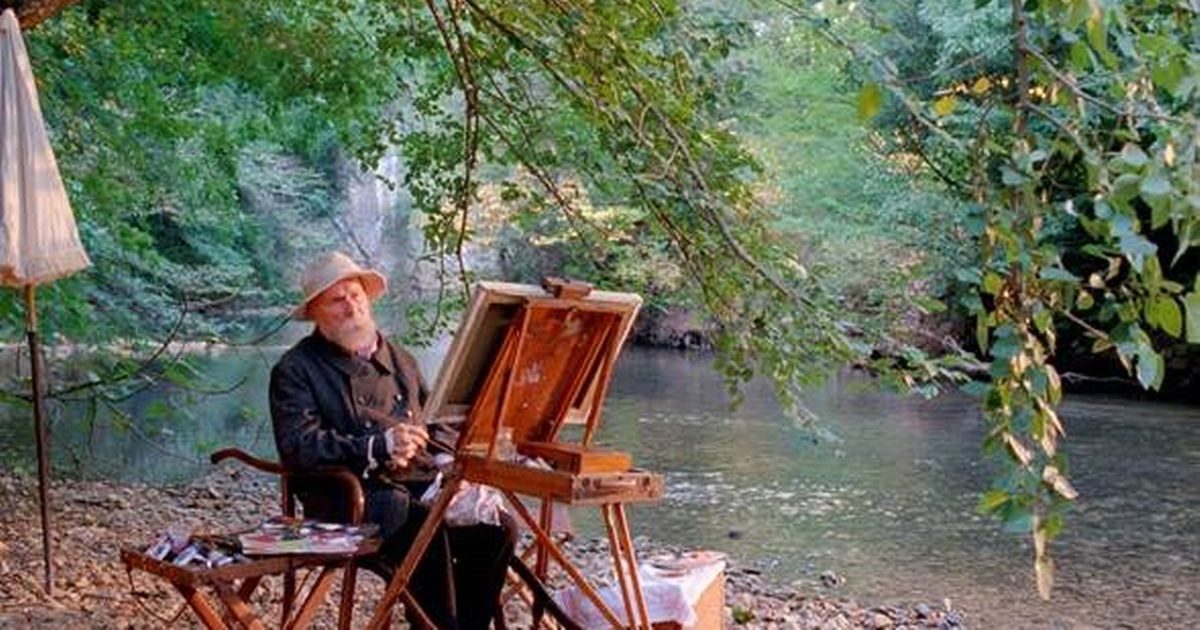

The film is a gentle, even pensive affair – Catherine, played with fiery intensity by Christa Theret, makes her first appearance cycling through the vibrant, verdant French Riviera. Mark Lee Ping Bin’s cinematography succeeds magnificently in capturing the outstanding natural beauty of the landscape, a palette of rich multi-hued greens, the water-color sky.

As a work of cinema, Renoir feels appropriately painterly, striving, perhaps, the match the work of the great man himself, whose amiably crotchety portrayal by Michel Bouquet is one of the film’s delights.

As his father is contemplative, self-indulgent even, the younger Renoir, Jean, played with a boyish sort of reserve by Vincent Rotiers, is struggling to find his place in the world. Both he and Auguste have their wounds, literal and otherwise – the elder, wheelchair-bound, suffers from debilitating arthritis that requires his hands be bathed and swaddled; the younger, a wounded leg that demands the use of crutches – but they are, nevertheless, remarkably similar in temperament.

Catherine sparks something in both father and son, and indeed, the film, which sensually peruses her nude form, outstretched beneath the artist’s canvas.

In that the events of Renoir precede his film-making career, we are denied an understanding of who Jean Renoir was as an artist, or, indeed, his presumably deep-felt motivations for making film his life’s work. Catherine declares ambitions of being an actress – the role of muse chafes at her; she smashes a number of Auguste Renoir’s hand-painted plates in a fit of pique – and, sequestered with Jean, the two of them admire a flickering projection. Given the medium, it’s a shame that Jean’s future career is given so little development except as a response to his father’s dicta.

The film has a hazy, almost canicular feel to it’ set in the eternal summer of Auguste’s dying days. Jean longs to return to the front line; he picks a fight with a hawker who suggests there’s a living to be made in recovering and repatriating the bodies of fallen soldiers. It takes Catherine and all her vivacity to make him appreciate his father’s extollment of the virtues of the flesh, of art as an antidote to suffering.

Auguste, whose eyes and hands, the tools of his trade, are failing him, is made the voice of authority; Jean has nothing to counter him but pragmatism.

Renoir is a sumptuous, sun-drenched picture that harnesses the beauty and power of its subjects’ work, but one that revels too much in the artistic, aesthetic qualities of the form. Lingering and occasionally soporific, a portrait it captures all involved, but only ever in the shade of the figure of Auguste. As a landscape, though, capturing a time and a place, the film is often sublime.

There’s an undercurrent of drama to Renoir that rises to the surface like an aquifer whenever art meets life, but too often the forces are held apart. Despite this, if you’re in a reflective and forgiving mood, there’s a lot to admire here.