(2 / 5)

(2 / 5)

Great literary adaptations can occur in the most unexpected of places.

Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird is widely regarded as one of the greatest works of fiction ever written and its 1962 adaptation starring Gregory Peck comes in at #25 on the AFI’s list of greatest American movies. The second film on that list, however – Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather – derived from Mario Puzo’s 1969 novel; a brilliant piece of mass-market pulp but hardly a work of unbridled genius.

Of course, there are different criteria that go into making a great novel and a great film; the literariness of the former can often prove detrimental to the latter. To this extent, James Joyce’s wordily thicketed Ulysses, for instance, is basically un-adaptable. Sometimes what’s on the page simply can’t be translated onto the screen, at least not in a faithful or coherent fashion.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, arguably the great American novel, has been previously adapted to the screen four times: as a silent film in 1926 (now lost), with Alan Ladd and Betty Field in 1949, with Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, and with Toby Stephens and Mira Sorvino in 2000. None of them are classics; in fact, none of the final three are even particularly good.

There is, however, one worthwhile film that bears a notable resemblance to Fitzgerald’s masterwork, none other than Citizen Kane, which appears in pole position on AFI’s list. Both Kane and Gatsby are self-made men who, in different ways, confuse love with ownership and are ultimately destroyed by unfulfillable passions. While Kane is a loosely veiled attack on famed “yellow” newspaperman William Randolph Hearst, Gatsby is a critique of a much grander theme: the American dream itself.

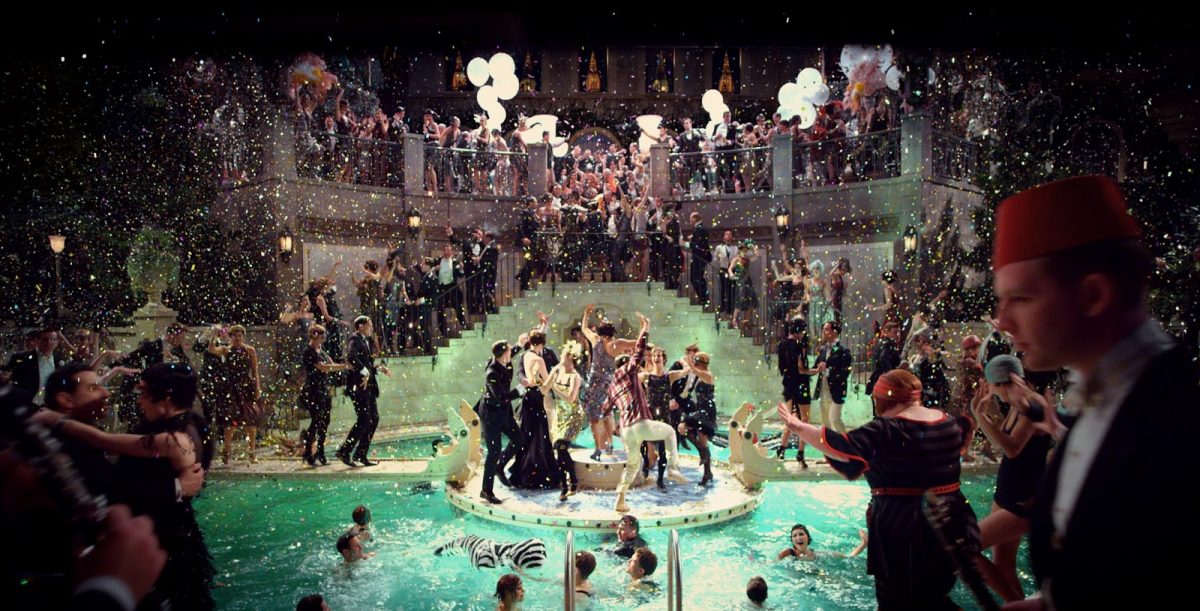

Superficially a tale of romance and excess, the novel would seem to be a unique fit for Baz Luhrmann, who, with his jump cuts and crane shots, is to period drama what Michael Bay is to teenage actioners. The story, in a gilded nutshell, is that of Nick Carraway (Tobey Maguire), a Yale graduate and war veteran turns bondsman, who finds himself embroiled in the affairs of the mysterious Jay Gatsby (Leonard DiCaprio), a notorious and obscenely wealthy socialite.

Presented by Nick as a biographical novel he is writing during his recovery in a sanatorium years later, The Great Gatsby is desperate to stress its literary roots. Occasionally Carraway’s narration spills out onto the screen in great cursive letters, but the sheer hallucinatory sumptuousness of the film simply overwhelms attempt at recapturing Fitzgerald’s prose.

If Apocalypse Now was, as Coppola claimed, more than simply a film about Vietnam but Vietnam itself, then The Great Gatsby is not merely a film about New York in the Roaring Twenties: it is the embodiment of the time and place. From Times Square with its grand billboard of the Ziegfried Follies to Gatsby’s Art Deco palace, you are fully immersed in that world, and the modern soundtrack, as opposed to creating distance, makes the mise en scene seem pressing and urgent.

The film, however, lives and dies by its performances and they are, bar one, uniformly excellent. Maguire’s Nick is a wide-eyed every-man swept away on the tide of the age. He is, in Fitzgerald’s own words, part of it all yet always an observer, within and without, yet never too, too passive as to lose your interest. Joel Edgerton’s Tom Buchanan, meanwhile, one of those doing the sweeping, is a self-righteous brute; a self-made man who dominates through sheer physical presence.

Leonard DiCaprio’s Gatsby is, for all it’s glitz and glam, the film’s greatest creation. One of the best and most consistent actors now at work, DiCaprio captures the character’s hollow “old sport” charm beneath which lies an all-consuming desire. Gatsby is a man defined by his wants – he has assembled the lavish world around him as a means to an end – and all he wants is Daisy (Carey Mulligan).

Daisy is Nick’s cousin, Tom’s wife, and Gatsby’s one true desire, and it is here unfortunately that the film is at its weakest. Daisy is the object of many men’s desire and, being so constantly acted upon, requires a great sense of interiority to prevent from seeming like just, well, contested property. Mulligan, for all her beauty, simply doesn’t provide this. Loathe though I am to say it, she feels miscast.

Overall, the film is by no means a disaster but feels like something of a misfire. In this way, The Great Gatsby is perhaps less like the book than the man himself, a grand edifice with a single purpose, striving towards that distant light which remains forever out of reach. In trying to emulate Fitzgerald’s novel, the film sets itself an impossible standard: prose is equipped to deal with shallowness as a theme while Luhrmann’s adaptation simply becomes mired in it.